A Child from South Italy, a novel

The Ghosts of youth

From chapter 2 till chapter 6.

I repeat what I said in the first post: No one italian publisher liked “A child from South Italy”. It is, so to speak, an orphan. I am looking for a publisher.

Your opinion, whatever it is, is important for me. Thank you.

A Child from South Italy

II

The station at Stìdero had come alive with a group of friends and acquaintances who had come to see young Nicolò off. When the train was leaving, youthful arms were outstretched, all waving together. Nicolò managed to get hold of two at a time and give them a squeeze, amongst them also Amedeo’s arms, and when the train had already started moving, Amedeo shouted:

“Write to me!”

And he replied:

“I’ve already forgotten everything we ever learnt at school. I’ve forgotten how to write.”

Then he gave a last salute from the train window to the group of friends who were still waving on the platform, he glanced up at the mountains of Fiermonte and lastly at Mount Agave, and then he sat down inside the compartment with a heavy heart and his face lined with tears, in spite of the fact that he had promised himself not to cry.

There were other people on the platform apart from the noisy group of friends. There were two gentlemen, one taller than the other, who was also somewhat stout, and they were strolling along, arm in arm.

“Another ragamuffin is leaving,” said the shorter one.

“Perhaps they will all go, half-starved as they are,” replied the other.

“But Mr. Lazzaro doesn’t want the young people to go.”

“And why should he? He gets good use out of these peasants. The more there are, the less he needs to pay them and the richer he gets. As far as I’m concerned, they can all drop dead. If they weren’t here getting between our feet, we’d all be able to breathe more easily.”

Amongst those who had gone to wave Nicolò off at the station, only his cousin Amedeo belonged to his closer family. When Nicolò left Calvario, apart from Amedeo, only his mother was still living there.

Shortly before, they had killed his brother whilst he was doing his military service. One Sunday afternoon, in order to get away from the boredom of the barracks, a drunken officer had got into a tank and started to drive it around the parade ground and the surrounding streets. He had lost control and ended up crashing it into the wall of the munitions depot. Nicolò’s brother was brought out from the rubble dead.

His sister had fallen in love with a married man when she was sixteen. One day, when he came back from hunting, he found his wife in bed with a travelling hawker, and without thinking twice, he shot both of them. He escaped into the Fiermonte mountains and became a bandit. Nicolò’s sister, consumed by her love for him, ran away with him and remained at his side until he was captured. After that, she didn’t want to return to Calvario and she disappeared.

Nicolò, the youngest of the three siblings, wasn’t born by chance, but because of a plan his parents had dreamed up. They told themselves that, if it turned out to be a girl, they would find a way of letting her die (such things happened quite often in the region of Schidiscita, where Nicolò was born), because they couldn’t have afforded to feed another child, nor one day in the future, find a dowry for her; but if it was a boy, they would bring him up to help them in their old age.

It was a boy, but things didn’t turn out as his parents had planned. He was only two years old when they killed his father. An ambush, a shot, a bullet, a coffin, tears, hysterics and beatings of the breast; then the funeral of a murdered man, the cemetery, the hole in the ground, the pall bearers, the soil, the end of a human being.

The murderer, a brutish fellow, managed to get away, which was very common in those parts. Nicolò’s mother took to looking for him with a carving knife in her bag with the idea of avenging her murdered husband before the murderer was arrested.

That didn’t happen; the police put him in handcuffs before she found him. So the mother decided that, when the murderer was released from prison, Nicolò would be the one to take revenge.

But that didn’t happen, either. Nicolò didn’t become a killer at the wish of his mother, nor for the sake of a vendetta, another thing which was very common in the region of Schidiscita; neither did he stay to help his mother in her old age, but he left to go and live in France, with a long-lost aunt, while he was still a boy.

That evening, the evening when he left for France, his mother hadn’t come to the station. She was against him going. She had been the embodiment of the devil all day. She had cried and cursed her son and her fate. Only at the last minute, and only begrudgingly, had she packed his case and prepared something for him to eat during the journey.

When it was time to go, Nicolò went to face her, tense, with his arms held stiffly at his sides like two sticks. He looked straight ahead, hoping that she would say something to him, that she would give him a hug at least this once.

But she didn’t do either. She gave him a black look and sent him on his way with a contemptuous movement of the hand, saying,

“You’re not my son any longer. You don’t exist for me any more. You can go and join your sister, or even die.”

Now the train had disappeared. Those who had come to say goodbye had left the station and taken the road home.

The two gentlemen were still strolling up and down the platform, taking in the salubrious sea air, enjoying the blue sky which seemed to come right down to touch their heads and discussing the bad luck of poor people and the good luck of the rich.

All this had taken place in the early 1950s. Since then, many years had passed, many things had happened, thought Nicolò, while he walked along the path which led to his cousin’s house.

III

“So,” says Amedeo, “are you going to let me choose?”

“You can trust him, cousin,” says his wife, Lucia. “He’s an expert. He’s spent more time match-making than doing his real job.”

“That’s right,” Amedeo confirms what she says. “I don’t know how, but marrying people off comes easy to me.”

“Why don’t you start a dating agency?” Nicolò suggests.

“This isn’t the right place,” says Lucia.

“Anyway, I haven’t come back to get married. I don’t know the women from around here, and I wouldn’t know how to live with one, if it weren’t just as male and female.”

“Correct!” exclaims Amedeo. “That’s all you need to know. Maybe it’s the best way to live with a woman, because when there’s too much talking between men and women, your sexual appetite goes out of the window.”

“You should practise what you preach. Between us there’s practically nothing of either,” escapes from Lucia.

She is sitting upright, as slim as an olive leaf. She’s wearing her hair in a net, and, as it is very thick hair, her head seems too large for her body. She has a sweet face, pleasing, relaxed, resigned. She has cooked an excellent dinner and served the dishes with charm. When she speaks, her words came out naturally.

“You see,” Amedeo retorts, flushing, “you only need to open your mouth and you immediately become the target, especially when it’s your wife who knows all your weak points.”

Lucia understands that she has said something she shouldn’t have and tries to make things better. “Your cousin has travelled throughout the world and knows that we’re only joking.”

“Of course, my dear, of course he knows!” says Amedeo with bitter irony.

At this point, Erica and Pietro, the two children come to say goodnight to their parents and their uncle who has arrived out of the blue, whom they had never heard anybody mention before.

They had spoken about all sorts of things during dinner. A lot of folk, Amedeo said, had left Calvario. Some, after having spent time in northern Italy or other countries, and after having made some money, were coming back to build houses. But some people had died before the house had been finished, as had happened to Malavoglia and to Barricchio; both of these, when they had spent their earnings, had gone back to earn some more money so that they could continue, but the works had been left unfinished.

“They both died before finishing their houses. Malavoglia was squashed by a crane and Barricchio died in hospital, but nobody knows what of. The houses are still there, as they left them, with their walls half built.

“There’s nothing in Calvario. We survive by scraping a living from what nature gives us: some fruit or a bit of wheat.”

Among the local Calvario population, there was the family Dritto, Lucia said. A large family. Practically all the younger generation were married. He, Dritto himself, a hawker, was stuck-up and thought he was goodness knows what. It was better not to have anything to do with him. The new house, which Nicolò had seen when he arrived, belonged to one of the sons, the eldest, who had married and lived there with his wife and daughter.

Nicolò, in his turn, told them about the work he had done in his old house that afternoon, of the spider webs, the mice, the photo, of the bed covered in dust and the feeling he had had upon seeing the old place.

Lucia asked if he needed anything for that night and he said that, just for one night, he could sleep anywhere and the next day he would go to town to buy what was necessary.

He asked Amedeo if he knew anybody who could paint the house, put in a bathroom, put down a carpet in the bathroom, as he didn’t really like the tiles, and cast an eye over both the interior and exterior for any repairs that needed to be done.

His cousin promised to take care of it.

The night was clear. Over them, the sky was profound, far away, full of stars which seemed to lose themselves in the immeasurable distance of its mystery.

“Daylight blinds us,” went through Nicolò’s mind, “and night-time illuminates us.” And he smiled up at the round lights sparkling above him.

A slight breeze brushed their faces, still overwhelmed by the unexpected events.

Amedeo continued, “Whoever would have thought it!” without daring to ask Nicolò all the questions he would have liked to.

And it was late. All three understood that the evening had come to an end.

Nicolò’s house was a few kilometres from where his cousins lived. He would have preferred to walk, but Amedeo insisted on taking him in his car. Of course he wanted to make use of the recently-built road.

IV

When Amedeo had left him, Nicolò went into the house, approached the fireplace with decided steps, took the whip off the wall and laid down with it on the made bed. The half-light of the moon filtered through the cracks of the windows and he started examining and touching the whip. Perhaps, if he looked more closely, in spite of the poor light, he would still be able to see the odd flake of his own skin on the whip. That afternoon, when he had first glimpsed it, it had made him shudder, and he hadn’t wanted to touch it. Now, though, how could he not? Conflicting feelings and memories stirred in him, exploding in his brain like a flash of lightning in the night, lighting up the dark sky with images, ghosts of his childhood.

His mother receives a letter from Stìdero, the largest village in the area, in which she is told that she must send Nicolò to school. But she doesn’t want to, she can’t see the necessity, the use, you can’t live from books, living in the country as they do. The authorities make it clear that she has no choice.

She gives in only after a great deal of resistance. The school is a long way from their home. But first of all, she must find a way to buy the necessary kit, which causes a great deal of problems. In spite of the fact that four years have gone by, she is still in debt over her husband’s funeral, she feels buried by a mountain of debts. But she has no choice. In addition to the exercise books, she buys him pencils, pens and ink, even a pair of shorts and a pair of shoes. She has the cobbler put nails in the soles, they are of hard, heavy-duty leather, and large enough so that he can wear them for years to come. Nicolò’s feet, for the very first time, make acquaintance with shoes.

He goes to school. He writes his first lines, crookedly. He learns to write them straight, he learns the alphabet, to write his own name, to say some words in Italian rather than his dialect, to count to a hundred without making a mistake.

He starts to do his homework. He understands that it’s better to do it as soon as he arrives home, while it’s still fresh in his mind, when he can still remember the teacher’s explanations. His mother wants him to eat something, but he refuses, he prefers to do his homework first. Food has become scarce and sometimes they only eat once a day. His mother doesn’t insist, but when she is calm and there is something to eat, she refills his plate with beans and he devours them with a couple of slices of rye bread. White bread is only eaten, if at all, on feast days.

His brother and his sister, both of them illiterate and older than Nicolò, can’t understand his mania for studying. They often tease him, they pull faces at him, tell him he should look after the sheep and goats rather than go to school. Whenever he manages, he ignores them. When he can’t stand it any more, he lashes out with his fists and feet and blows are exchanged.

He continues to go to school and moves up into the second grade. He sits in the front row and always listens attentively to what the teacher says. He squabbles with a classmate who pinches him. The teacher sends them outside. Nicolò is not annoyed with him, even if he finds the punishment unjust.

One day, just before the end of school, a badly behaved boy throws something at the teacher. It hits him in the face. The teacher can’t see very well, so doesn’t know who threw it. Whatever it was came from there, right where Nicolò is sitting, and the teacher thinks it was him. In his anger, he breaks the cane, which he keeps leaning in the corner, across the palms of Nicolò’s hands. Everybody in the class is laughing whilst he is being punished. The guilty party doesn’t own up. Such cowardice!

After a while, the palms of his hands swell up and look like two loaves of bread. The pain is killing him. But Nicolò doesn’t cry even though there are tears in his eyes.

At home, that day, he breaks a glass because he can’t keep hold of it properly.

His mother, for the first time since he started going to school, threatens never to let him go again, and thinks that the caning will have been deserved.

He doesn’t react, he hides his tears, he tries to put up with the pain, holds his hands in cold water. He doesn’t go to school for two days.

Then he goes back. He is second best in the class. The best is the son of a gentleman who knows how to read and write and who works at the town hall in Stìdero. Nicolò discovers that he enjoys learning. He never misses a lesson. He goes to school even when the weather is bad, when there is a storm, when he doesn’t feel very well. He openly argues with his mother when she threatens to not let him go to school any longer.

He never goes out to play football with the other boys now, he stays at home doing his exercises. The other boys, just like his brother, tease him, and call him a swot. He doesn’t mind. And when he can’t stand it any more, he gets involved in fights. Sometimes he comes back from school in a bad way, blood running from his nose. He says that he fell down. He washes himself, and suffers in silence. He knows that if he cries, his mother will give him something to cry about.

He moves up into the third grade. He is very satisfied, even happy. Nobody at home, though, neither his mother nor his brother and sister, share his jubilation. They just ignore him. He notices it, but does not beg for their attention. He is only happy to be allowed to go to school.

He continues to do his jobs about the house. He goes to collect wood, to fetch water from the fountain, he takes the sheep and goats to pasture, feeds the pig, cleans out the pens and the sty. These are the conditions if he wants to have the morning free for school. He doesn’t complain, and manages to do everything. When he takes the animals to pasture, he takes his books with him, and reads. While he’s doing other jobs, he goes over his schoolwork in his mind.

He loves doing multiplications, divisions and subtractions. At school, when the teacher tests his tables, it’s a real number ping-pong going back and forth between him and the teacher. Nicolò never makes a mistake no matter how many traps the teacher sets to catch him out.

He begins to have problems with his shoes. He doesn’t tell his mother, because she doesn’t have the money to buy him any new ones, and he’s not interested in being told for the umpteenth time that he shouldn’t be going to school. However, pupils are not allowed to enter the classroom barefoot.

So he limps. He cuts the shoes where they pinch him. His mother notices and beats him black and blue. She’s not interested in excuses. He puts up with this physical violence in silent resentment.

The teacher understands why his pupil is hobbling and brings him a pair of ankle boots, second-hand, but made of soft, smooth leather. Nicolò is embarrassed, but he accepts and thanks the teacher.

He only makes very few mistakes in his dictations, even fewer in his summaries, he describes his days using the correct verb tenses, writes short compositions, is given good grades and is well liked by the teacher.

He doesn’t care if his schoolmates call him a swot. At home, his brother and sister still tease him, especially when he tries to speak in Italian rather than dialect. He gives up any pleasure, any pastime to have time to do his homework and prepare his lessons.

He comes second again. The best in class this time is a lame boy, very intelligent, but also much older than Nicolò. The teacher gives him the book “Heart: a Schoolboy’s Journal” by De Amicis.

Once he has finished his homework and all his chores, Nicolò tries to read the book. He can’t understand all of the words, and he doesn’t have a dictionary, because his mother can’t afford to buy him one. It doesn’t matter, he reads it just the same. He would like to read until late in the evening, but he can’t because there isn’t any light. The oil lamp must be saved for emergencies or when visitors come.

He finds out where his mother keeps the torch, so he takes it and tries to read under the covers while the others are asleep. His mother finds him, takes the torch away and hides it.

A few weeks later, he sets fire to the bed sheet trying to read by the light of a candle stump.

This time, his mother really lays into him. Because of the beating, he has to stay at home a few days. When he goes back to school, the teacher scolds him. He doesn’t say why he was absent, he bends his head, tears in his eyes.

He passes the end of year exams with top marks, in the following year, he will be going up to the fourth grade in Stìdero. That day, Nicolò comes back from school with his heart bursting with joy. He would love to share this happy moment with somebody. He says, “Mamma, I’ve …” and before he can finish what he is saying, she bawls him out because there isn’t any water in the house. So, neither his mother, nor his brother or sister, who all know about the exams, ask him whether he will be moving up a grade. They pretend not to notice his feelings. He observes them for a moment. But he is well used to passing from joy to sorrow, to pain. He doesn’t complain, he doesn’t say anything. In silence, repressing his anger, he grabs a couple of carobs from a basket, bites into one, takes the earthenware jug, and the bucket, and goes to fetch water from the fountain.

The new school year has started, but his seat in the classroom stays empty. His mother, authoritarian and imperious as she is, passes sentence:

“You’ve finished with school. Now you have to work and earn some money. I only went to school a few months and I learnt to write letters to your father, God rest his soul, when he was away in the war. You’ve gone to school for three years. Much too long. I can’t use a professor around here. Now it’s time to start working.”

“But Mamma,” Nicolò implores, throwing himself at her feet, “let me go to school. Oh Mamma, oh, I beg you, I beg you!”

“You can forget it!” she replies giving him a kick to rid herself of him.

“I beg you …”

“Will you get away from my feet?”

Nicolò doesn’t go to school. He isn’t allowed. He can’t fight against his mother’s will.

One day, he escapes from home and runs to Stìdero with no shoes on and without his satchel, to look for the school. He waits behind the gate with his face streaked with tears, trying to hold back his sobs. He can hear the teacher talking. He listens. The voice is new to him, captivating. This teacher should be guiding him, teaching him new things. He hears the ring of the bell, the noise of the desks, the din of the pupils as they rush to the door. He just manages to hide. He sees two boys who were in his class the previous year. The last to come out is the teacher. He’s never seen him before. He is short, middle-aged, bewhiskered, with rosy cheeks and is carrying a large briefcase. He doesn’t have the courage to introduce himself. And even so, what good would it do? He stays where he is, unobserved. The others pass him by, but don’t notice him, and move off. Everything is silent, like a desert. Nicolò comes out of his hiding place. He stumbles, but doesn’t fall. He starts sobbing.

He wants to see the classroom. The door is open. He goes in, sees the enormous map on the wall, the words written on the blackboard. He stares at the teacher’s desk, the walls, everything. He is consumed by sadness, wants to cry, to scream. He feels a destructiveness rising inside him, he wants to break everything he can see there. He kicks one of the desks. He can’t cope any more. He bursts out crying, and is inconsolable.

He just manages to crawl out of the classroom and get to the street, but doesn’t go back home. Mechanically, his legs accelerate, he starts to trot, to run. He runs as fast as he can, not knowing where he is going. He crosses roads, streets, alleyways. He finishes on the main road, straight and lonely, never ending. He sees a turning on his right. He takes it, still running, over a level crossing, he ends up in a park, and then on the beach. He stops, enchanted. He looks at the sea. It’s the first time he has ever seen it so close. The immense space which opens up across the smooth blue bewitches him, but simultaneously, it intimidates him. He is tired to death, he can’t stay upright any longer and throws himself down on the ground. The dusty sand fills his mouth and nose. It tastes unpleasant. He spits. He starts to groan. Nobody hears him, nobody can see him, the only witnesses are his sandy bed, the sea, the beach and the sky.

He doesn’t go home that day, nor the next. He spends two nights in the park, hidden behind a hedge.

The second night, while he’s studying the heavens above him, full of stars, he feels shaken, a lump in his throat. He is stiff, and tries to curl up as much as possible. He’s scared, trembling, eyes wide open, he senses, understands, is finally utterly convinced that he is being deprived of an education in the most brutal manner, an education which would have helped him grow, to understand, and at that moment, he bursts into a fit of weeping, long and desperate. Exhausted, beaten, unhappy, his heart bursting with pain, he falls asleep still sobbing, the wind blowing through the bushes and over his body.

On the evening of the third day when he returns to Calvario, worn out and starving hungry, he discovers that the village is up in arms. His brother and sister are out looking for him. When his mother sees him, pale with anger, she takes down the whip, the one Nicolò is holding in his hands now, and comes towards him. He knows what it means. He’s had plenty of experience before. He’s not scared of her, especially not now that he’s spent two nights confronting his own fears while hiding in the bushes. Nothing can scare him now, least of all his mother’s anger.

When she sees that her prey cannot escape, she launches herself at him with a wild shriek of fury. The whip whistles through the air and hits him all over with such violence, but he doesn’t run away, he doesn’t scream, he doesn’t cry. While the whip is lashing him with monstrous ferocity, Nicolò dares to look his angry mother straight in the face, with indifference but also with love.

After a while, his legs buckle beneath him and he falls to the ground. But that isn’t enough for the woman who brought him into this world. As if in a frenzy, no pity in her heart, she continues to beat the little heap of flesh lying almost motionless on the ground.

Some farmers working in the fields nearby hear the screams and come running, take him away from her, try to calm her down.

The woman, furious, is screeching and cursing, consumed by her madness, she screams that she’s going to murder him. She goes into the house, takes his text books, exercise books, pencils, pens and satchel into the kitchen and throws them on the fire. And she screams,

“We brought him into this world to help us when we were old, and now the little devil wants to have it all his own way. I’ve told him that school is over. I gave birth to him, but I can also kill him!”

When Nicolò has recovered from the beating, he changes, and changes so that you can hardly recognise him. He hates books and he hates the others who are still going to school. Whenever he sees a schoolboy, first he lets fly at him with his catapult, then throws himself upon him hissing curses in dialect and punching and hitting him with a stick.

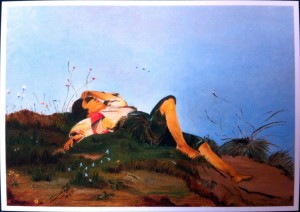

For months, he is in constant battle with the local lads. He takes umbrage at anybody speaking Italian. Drunk on his sense of solitude and fury, he spends his time climbing trees like an ape, like Tarzan, he jumps from branch to branch of the oak tree standing in front of the house, he runs like the wind through the fields, from one hill to another, he staggers to the top of Mount Agave, the highest mountain in the area. He throws himself on the ground, pushing his fingers and toes into the soil, often with his face covered in tears, he stays like that in silence, his eyes closed, tasting the affectionate tickle of the wind on his skin and listening to the light rustle which reaches his ears. Then he turns onto his back, stretches a leg, puts a hand in front of his eyes to stop the glare of the sun so he can study the heavens above him at his ease.

Ignorant and lost in a hard and indifferent world, he observes in wonder and awe the infinity opening up to him. This sight calms him down, quietens him and finally a smile spreads across his tear-streaked face: Nicolò is smiling at the sky.

He rarely approaches travellers, hunters, shepherds or others he sees. He has become a savage, he watches them from a distance as if they were dangerous animals better not to go near.

For days he doesn’t open his mouth, only to the animals in his care. He hates his brother and sister, he hates his mother, although not always. The feelings he has for her, in spite of everything, are painful, conflicting. He feels, though, that between him, his mother and his siblings, there is no means of communication. The aggressive language they use to talk to each other is more like that of beasts rather than of human beings.

Nicolò has developed a sadistic interest in destroying birds’ nests, ant hills, spider webs, killing lizards, skinning frogs alive, but he keeps clear of snakes. He’s scared of snakes. Those long black ones slithering across the earth horrify him, terrify him. His weapon of choice is his catapult. He never misses. He is able to hit a chaffinch at fifteen metres. Except for snakes, he has become the terror of all other animals. They seem to know him, to sense the danger, because, as soon as they see him, they fly away or run off at breakneck speed.

Only with Peppe, the farmer, does he occasionally exchange a couple of words, a friendly gesture. Peppe has a way of being calm, cheerful, restful. He doesn’t raise his voice when he speaks, as do most other people in those parts, and Nicolò appreciates this. Yes, he likes Peppe. And even if he doesn’t often approach him, he often spies on him from a distance while he works in his fields.

In this way, slowly but surely, Nicolò manages to forget everything he learnt at school and become light, weightless, like the plants, like the animals, like the air he breathes.

One day, an emigrant comes back to live in Calvario. He has a pretty little girl with blonde hair, just like her mother, who comes from the north. When she opens her mouth, out comes a sweet, delicate, caressing little voice. She doesn’t know the local dialect and only speaks Italian.

Right from the start, Nicolò keeps his eye on her, he hates her, especially when he hears her speaking Italian. He would like to slap her, make her cry, just like the birds he hits with his catapult before they die.

But slowly, the little girl, with her delicate, sweet little voice, transforms him, wins him over. He sits at the side of the road in order to see her pass by with her parents. Sometimes he pretends to need to go the same way so that he can hear her speak, see her. When he thinks of her, he feels different and all his savage cruelty is transformed into tenderness. And it is the little blonde girl from the north who guides him back towards reading.

One time, at the fountain, where he goes to fetch the water, he finds an old newspaper which has been forgotten there. He picks it up, folds it, puts it in his pocket and when he has the opportunity, he reads it out loud. He punches himself in the head when he realises that he isn’t pronouncing certain words correctly. He repeats them, keeping on until he can do it properly.

He starts speaking Italian, the national language, with his sheep, the goats, the dog, the pig, with all the local animals, even with Peppe to see if the farmer can understand him.

Bit by bit, Nicolò starts reading everything he can lay his hands on: newspapers, comics, books. He wants to learn how to speak Italian, because, sooner or later, he wants to speak with her, the little blonde girl who comes from the north. She however, will never know Nicolò and even less about the effect she has had on him.

Later on, things change again. He starts to work. His first job is with a goatherd, where he has to look after the goats. Then he becomes an errand boy who carries drinks to the men working on the roads, after which he goes to work for Mr. Lazzaro and then on the building sites, and begins to bring home a bit of money, which helps to satisfy his mother.

“Yes, that’s how it was!” says Nicolò as if he were speaking to somebody else, and the whip slips out of his hand. He closes his eyes and tries to go to sleep.

V

It’s daylight. Noises from motorbikes, scooters, bicycles, mules, carts, donkeys, a few cars: the people of Calvario and the surrounding villages going to work, on their daily business.

Nicolò is lying on the bed, fully dressed. He hasn’t slept very well. He shakes himself and gets up. He feels dopey. He looks around, surprised. He finds something he didn’t find yesterday. At the bottom of a trunk, there is a scarf belonging to his mother, two photos, one of his father during the war, and one of his brother, also in uniform. No sign of the sister. He realises he really wants a cup of coffee, something warm in his stomach. But there is nothing in the house, only memories. This place wakes memories of a world which he thought he had buried. He doesn’t want to remember, not for the moment. He washes his face hurriedly, straightens his hair and leaves the house.

He reaches Stìdero by bus two hours later. He goes about some errands. He rents a car while he waits for a new one which he has bought to arrive. He goes to the police station to ask them if he can drive with a foreign driving licence. He can, but he must change it in the future. They bury him under a pile of bureaucracy which he’ll have to fill out. While they are giving him all this information, he thinks it might be better to be fined day by day rather than bother with such a pile of paperwork and the medical examinations necessary.

He goes to the town hall. The clerk he needs to see is not there. They tell him he should be coming any minute now. But he doesn’t come. He waits. He continues to wait. Nobody. He carries on waiting, still nobody. He is tired, irritated, frustrated. He leaves.

He walks around the streets of Stìdero with no particular aim. He meets people. But he doesn’t know anybody. He goes into a bar. As soon as he crosses the threshold, a man sitting at a table stands up and comes towards him. At every step he takes, his smile widens. When he reaches him, he says:

“Is it a ghost, a hallucination or a childhood friend standing in front of me?”

It’s Michele, his old best friend. Michele Michele Michele… He can still see Michele’s youthful arms stretched towards him at the station, he sees, in a flash, their youth together. And now, Michele in the shape of a grown man standing in front of him!

They look at each other, give each other a hug.

“I’m very happy to see you,” says Nicolò.

“Me too,” echoes Michele.

They sit down, order coffee.

“Where are you living?” asks Michele.

“Do you want to know where I was living, or where I’m living now?”

“Both.”

“First in Sydney, now I’m at my mother’s house.”

“When did you arrive?”

“Yesterday.”

“With wife and children?”

“I haven’t got either,” Nicolò finds it easy to say.

“Neither have I ever got married. We can start again like in old times and find ourselves a wife, only you and me this time.”

That “only you and me” brings something back to mind for Nicolò from many years ago.

They often met, went out together, had their Sunday stroll along the Corso Cavour, made eyes at the girls and were part of an inseparable trio: Michele, Vincenzo, Nicolò. Michele, at eighteen, was the eldest, Vincenzo was sixteen and Nicolò only just fourteen.

Vincenzo was in love with a girl of the same age as him. She had lost her mother when she was little and lived with her father, who you never saw out and about and nobody really knew anything about. Bit by bit, Vincenzo managed to persuade her to come out into the garden during the night, whilst her father was asleep. After a while, she realised that she was expecting a baby, and told him so.

Vincenzo was terrified by the news. He was still at school, too young, he couldn’t get married at that age, and he didn’t know what to do. And if his father had found out, he would have killed him. He refused to accept the baby as his. He even insulted the girl saying that it wasn’t his baby and she must have been with another boy!

One night, Maria Maddalena, that was her name, resolved the problem: whilst they were kissing, she put her hand into her pocket, gripped hold of a smooth, heavy object, and before he knew what was happening, she shot him point blank in the heart with her father’s gun.

“I think I know what you’re thinking about,” says Michele who has noticed the change in Nicolò’s expression. “And do you know she came out of prison a couple of months ago? I bumped into her in Stìdero the day before yesterday and I have to say, in spite of all those years in prison, she’s still beautiful, in fact, even more beautiful.”

“If you want to, why don’t you marry her?”

“Marry her! Me?”

“Yes, you!” Nicolò repeats and feels the old friendship suddenly explode inside him.

“Are you joking?” asks Michele staring at him, and it is as if they only parted company yesterday.

“Not at all. I think you could be happy together.”

“And why is that?”

Nicolò remembers that Michele liked Maria Maddalena a lot. He often teased Vincenzo saying that he was too young for Maddalena and that she needed an older man, like him. Vincenzo was not offended when Michele said such things, he just let him get on with it. Nicolò however, to start with, thought that Michele was joking, as did Vincenzo in all likelihood, but he wasn’t really. Michele wasn’t joking at all. He was jealous of Vincenzo, because he was in love with Maria Maddalena. Perhaps he had always loved her, always waited for her, she was always in his heart and he was always thinking about her.

“I can’t explain it to you, I’ve just got a feeling. Am I wrong?”

A shadow crosses Michele’s face. He says sadly, with a change of expression, “Even if you weren’t wrong, would it make any difference? Then was then, now is now. Then we were happily ignorant, today we’re more aware, we realise that time flies: even worse. We go on, bowed down by the cruelty of time, we watch our days decreasing while our innocent dreams have become relentless reality.”

“Ouch!” says Nicolò.

His friend looks at him thoughtfully, he drinks his coffee and opens a packet of cigarettes, offering one to Nicolò.

He refuses, he doesn’t smoke. He asks him, “Tell me about Stìdero.”

“What about it?”

“Bring me up to date.”

Michele seems a bit put off by such a request. However, after a moment’s reflection, he starts to tell his friend that everything is just like it was. Maybe not everything. Some people have changed their velvet trousers for denims, others have swapped their donkey for a bike, someone may have a scooter, a car, others, instead of working twelve hours a day now only work ten hours, then some people, instead of walking twenty kilometres in one day just to go to town, now take the bus and others, who don’t have the nerve to confront somebody else face to face, as used to be the custom, now ambush him and then still go to his funeral. The legal school attendance requirement is now no longer only five years’ elementary school, but has been extended to a further three years’ middle school. Some kids even go to the grammar school. But in spite of all this, nothing has really changed, nothing important, anyway.

“But surely there must have been some progress,” Nicolò insists.

“What progress? Progress which we have made ourselves, or progress that comes from outside?”

“What difference does it make?”

“What difference does it make? A lot!” Michele exclaims heatedly. “True progress, progress which counts, which helps us to grow, that’s progress which changes us on the inside. Progress made by the sweat of your brow. Around here, that kind of progress doesn’t exist.”

“Get away with you!” replies Nicolò. “I’ve just arrived and I’ve already seen new roads, buildings, orchards. Just think, in Calvario they’ve even got running water in their houses!”

“If you think that that is what changes people,” Michele says disappointedly, “you should think again!”

“In your opinion, what would it take to change the locals?”

In answer to this question, Michele becomes animated and comes out with a long diatribe, “People around here haven’t changed in centuries, so how could they change now? This is a weird place. Any culture has atrophied, has become like a massive block of granite, it’s impenetrable. Electricity, denim jeans, buses, cars, television, progress, in these parts, everything is transformed according to our mentality which is scarily antiquated and intransigent. All of these things have changed our lives from a material point of view, but not from a cultural one. Culture changes, improves, if old habits change, old traditions, but in this area, they are made of iron. No, let’s say stainless steel. At the technical college, even at the university, the few people who get there, they only go with the idea of getting a certificate which will enable them to earn more money, but not to widen their cultural horizons. The spirit of innovation hasn’t taken root in these parts, because people’s minds are like stagnant pond water. And don’t bother telling me about the few who have managed to distinguish themselves from the normal pathetic run-of-the-mill, because they firstly haven’t had any influence on the others, but are rather the children of excellence who are the exception to the rule. The reality is different, it’s a lack of intelligent and innovative minds which develop amongst civilised populations and which stagnate in those who are oppressed by ignorance and superstition. What do you think has changed? Here we’re governed by egoism and provincialism. There’s nothing that could change us. Our brains are pre-destined to be mean.”

There was a fellow near his house, Michele continues, who was continually in a rage with everything and everybody, especially with his own family. When he wasn’t beating his wife or children, he was beating his animals. He and the dog were always fighting with each other. Once, he bought himself a scooter and he ruined it within a couple of months. If it didn’t go, he kicked it and beat it. One day, when he was hitting it, he hurt his hand, and had to go to the doctor to have it treated. When he came back, this time using his other hand, he took a stick and started beating the poor scooter, just as if he were beating someone from his family, or one of his animals.

“So what can you expect from people like that?” Michele is angry. “I’ll tell you in a single word: nothing. Here, unless there’s some kind of massive revolution, everything will continue in the same sweet way, and the rest is just blah blah.”

Nicolò whistles and says “Now we’re really getting hot under the collar!”

“It’s only what I think.”

“Of course.”

“You’ll see.”

Nicolò looks at him, thinking, and remembers his friend who used to like reading, politics, and either alone, or with his father or friends, never missed a meeting when speakers came to Stìdero. He continues to observe him.

Michele shakes his head, looks back at Nicolò and asks: “Is there any special reason to bring you back to Stìdero?”

“I’m here,” he replies, “but at the moment, I can’t talk to you about it. And how are things with you?”

“There’s not a great deal to tell. I lost my father, I live with my mother, I’m a full-time small-holder and when I have time, I read.”

After a little, the two friends take their leave of each other, promising to meet up again as soon as possible.

VI

“Why, why, why, tell me why!” shouts Judy. “You’ve done your bit, you’ve done more than your bit, you’ve done a big bit. Why should you now, just now at this stage of your life, go crazy? I beg you, I beg you on my knees, forget all about it, forget this evil, black dream of yours and come to your senses, to reason, to reality, reality as it is here and now and not as it is over there, beyond the sea. You’ve changed since then and enormously. I love you, I can’t let you go just like that. This is foolishness, nothing else, only sheer foolishness,” and she starts shaking him.

Nicolò is sitting on the sofa, but his thoughts are elsewhere. The woman is trying to change his mind, this curse which won’t leave him alone. Despite the fact that she’s poking him, he seems not to hear her, he’s so absorbed in his thoughts. Judy shouts even louder, “Do you hear me?”

He wakes up bathed in perspiration, and exclaims, “Shit! She even gets on at me when I’m asleep.”

He doesn’t close his eyes again. He stays in bed. No noise, just utter silence. He begins to fantasise. Images from his recent life pass before his eyes. He watches them, develops them as if they were photographic negatives. At first, he enjoys it, then he gets tired of it, it irritates him, he wishes it would all go to the devil, he wants to sleep, but can’t.

An uncertain dawn begins to light the bedroom. He can hear the cock crowing, he can smell the perfume of the wild flowers, the meadows, he thinks he can see animals running around the field. It’s daybreak!

Bit by bit, his mind manages to brush away all the thoughts swarming through his mind, then the old memories of his childhood, the taste of his youth, make themselves felt. And like lightning in a dark sky, figures and images from his past life begin to come alive.

He remembers that he was so good with his catapult that they gave him the nickname David. He remembers that, one winter’s morning, he killed a sparrow with it. When he went to pick it up, the little bird’s heart was still beating. It was not yet fully-fledged, parts of the body were still not fully covered. He was attracted by the unfeathered parts, he could observe them, and started to stroke the soft plumes. He noticed that the sparrow’s eyes were watching him, terrified, asking him something that he couldn’t understand. He continued to stroke it. He looked for the injury he had inflicted: it was butchery! He softly pressed it against his chest, watching it, or rather, they were watching each other. He seemed to understand what the little bird was asking him:

“Why, why have you hurt me? What are you going to do with me now? Are you going to eat me? Will you give me to the cat? Will you leave me to rot?”

He seemed to see the little beak opening, chirruping:

“Don’t I have the right to live, too? Why did you have to fatally injure me, you murderer?”

At that moment, the sparrow’s heart gives up. Nicolò freezes, rooted to the spot, speechless, torn apart. He feels guilty, his hands are trembling, everything about him is trembling, he’s scared to look around, he feels that everything there – trees, rocks, mountains, animals – is accusing him, shouting “Murderer!” and he thinks he is one. Indeed, why kill it? He can’t find an answer. He feels that he is a killer, a piece of shit. He can’t go on like this. He gets angry, he pulls his own hair, grinds his teeth, wants to bring the sparrow back to life and knows he can’t, he wants to get into a fight with somebody, but with whom, if not with himself?

His anger continues to grip him, he’s bursting with it. He furiously hurls the sparrow against the trunk of an almond tree, he can hear the impact, and how the little thing falls to the ground. He runs to pick it up again. He doesn’t know what else to do, he starts stroking it again. He would love, oh how much he would love to be able to return it to life. But he can’t. He can’t! He is inconsolable.

With his heart bursting with remorse, which he can’t even explain to himself, he digs a hole and buries the little bird, silently promising it that he will never kill any other bird, nor animal and there, upon the grave so recently covered over, he destroys the weapon he used to kill the sparrow, his catapult.

The memories flood his mind.

As weedy as Baffone was in looks, he was just as courageous as a big man. That’s what everybody in Calvario said about him.

One day, a blast of wind knocked him off his feet and carried him through the air for quite a distance. He crashed into an oak tree and managed to hang on to a branch, twisting himself around it like a snake. He couldn’t move until the fury of the storm had abated.

After this event, Baffone was terrified of the wind. When he heard it blowing or saw the tops of the trees waving, his heart started to race. He began to fill his pockets with stones, and as if that weren’t enough, he also filled a long, narrow bag he had stitched together and which he always wore around his waist. He only felt really safe when the bag was full of stones.

He wasn’t truly from Calvario. He had an olive grove nearby and every year, during the season, he came along to harvest the olives.

One time, the wind and the rain had been rattling all night. The next morning, a poor, lonely widow from Calvario, Mrs Spellata, seeing that the weather was still looking threatening, thought that Baffone wouldn’t leave his fireside and so she would have the opportunity of stealing a basket of his olives.

But it didn’t work out like that. On that day, Baffone didn’t stay indoors. People knew that he was scared of the wind, and therefore he was certain that, if he didn’t go out, somebody would steal his olives. In addition, the bad weather had caused them to fall off the trees, so it would be even easier to pick them up off the ground.

Before leaving the house, he filled his pockets and his bag with stones, fixed it around his waist and then he went out.

As soon as he sets foot in his olive grove, he sees the thief. He waits a moment, watching her hurriedly picking up the olives and putting them in her basket. He recognises her, and considers what to do.

The widow, concentrated on what she’s doing, doesn’t notice Baffone. As the wind is not quite so strong any more, he partially unloads his stones and thus approaches her silently.

When the widow Spellata sees him right in front of her, with his big, knotted stick in his hand, she nearly faints. She leaves her basket where it is and runs away.

However, after only a short distance he catches hold of her. She tries to free herself from his grip, but isn’t able to. Baffone’s hands are like pincers and he holds her tight. But he still manages to give her a smack. She looks at him full of hatred and she tries to free herself. Nothing doing. She knows that, even though he’s small and skinny, he’s a puncher and she can’t expect any pity from him. She gathers all her strength and with one huge effort, she jerks herself free, pushes him off balance, and runs for her life.

Baffone jumps up, quickly relieves himself of the other stones which were still weighing him down, and runs after her, fit to burst with his anger.

They run through the fields. He’s soon on her heels. Widow Spellata feels him behind her, she can smell his breath, she stumbles, falls, and because it’s on a slope, she rolls down and lands against a big rock. She quickly jumps up. He is already there, grabs her again, tries to keep hold of her. She hits out about her. There is a wrangle. The widow, despite the fall and the smacks he has already given her, defends herself as if possessed by the devil. But the punches and kicks she tries to give him miss their mark, whilst his are more accurate and hit the target.

After a little, she’s exhausted, she falls to the ground a second time, she gets up, trying to stay on her feet, she protects her face from the punches, she feels as if she’s going to die, but he keeps on hitting her.

When Baffone realises that she is in his power – he knows full well that she’s poor and has no family – he sets about pushing and pulling her towards the trunk of an olive tree. He takes off his belt and straps her to the tree with it. The widow is finally immobilised and at his mercy. He notices that she’s not wearing any knickers, although that was normal for women in those parts.

He wants to punish her. She should be an example to others. With sadistic glee, he takes out a box of matches from his pocket and lights them, one after the other. He sets light to her pubic hair, without taking any notice of her screams. Widow Spellata faints. At this point, Baffone releases her, she falls to the ground at the foot of the tree. The hero, satisfied with himself, leaves her there and goes home.

Later, when she comes to her senses, the poor woman gets up with difficulty, more dead than alive, and goes home. She stays in bed for weeks, but doesn’t recover. A neighbour comes in to help her when she can and brings her something to eat.

Widow Spellata doesn’t ever recover. The embarrassment, the pain, the misery are stronger than any physical or moral strength she has left. She becomes seriously ill, she suffers, and dies.

And although everybody knew what had happened, nobody in Calvario ever said a word against the killer. And all that for a basket of olives!

Nicolò also remembers the experience he had the first time he went to work for Mr. Lazzaro.

He survived the first week at work, which was already a good sign according to those who worked at the furnace, because the majority of lads of his age – he was nine at the time – collapsed after only a couple of days. Nicolò collapsed, it was true, but only on the second day of the second week.

About two o’clock in the afternoon, while the sun was burning down, his body broken by the fatigue, he began to drag his feet. About half past three, for the first time since he had started working there, he began to stagger, and fell to the ground. He got up quickly, put the stones back in the bucket and once again began to drag the load towards the mouth of the furnace.

Another half hour, another hour, but how could he go on? The sun was still high in the sky and he couldn’t finish work before sunset. The only thing keeping him going was that he absolutely didn’t want people to say that “he didn’t survive at Lazzaro’s”. He wanted at least to be able to finish that day, he wouldn’t go to work the next day, he could find some excuse.

But in spite of his wanting to finish the day, he didn’t manage it. He fell heavily, crashing to the ground. The bucket he had been carrying on his right shoulder was the first to go, then his legs began to tremble and then he fell a moment later. He hit his head on two big, wedge-shaped stones. The blood filled his mouth. It tasted bitter. Then somebody picked him up and carried him away, washed his face, treated his wound, and let him rest until he had recovered a bit.

It wasn’t so much the physical pain which tormented him after the fall as the embarrassment of not doing his job at Lazzaro’s.

He is still reminiscing.

One winter’s evening, whilst his mother was out on an errand, she had left him at the house of a man who lived alone and who had been captured by the Germans during the war and taken to a concentration camp, perhaps Dachau. The man had managed to escape and after many misadventures, had returned home.

After his experiences in the concentration camp, it was said that he was unrecognisable. Before Dachau, he liked his beer, hunting, playing cards, the odd romantic affair, but then he had changed. He hardly ever went out and after his wife died, he practically stayed in the house, more or less like a hermit.

Nicolò had never seen him before.

That evening, when the mother knocked at the door, asking if he could look after her son for an hour or so, he looked at the boy for a while, then he took him by the hand and led him into the house, closed the door, and took him to the fireplace. He took a chair and told him, “Sit down and warm yourself. It’s cold.”

They spent a long time, or at least so it seemed to Nicolò, in silence, deathly silence. Then, just before the mother came back, the man said:

“Do you know that you’re richer than I am?”

Nicolò at first thought it was a strange question, but then he thought differently. He knew that the man wasn’t poor, but rather well off. He answered him, also using the familiar form of address:

“That’s not true, you’re richer than I am”.

“You’re mistaken.”

“I haven’t got anything, and I’m always hungry.”

“I’m not talking about material riches,” the man answered, “I mean in years. You’re a child, and compared to you, I’m old. You’ve still got many years ahead of you, I’ve only got a few. Do you understand now?”

“No!”

“All the worse for you!” said the older man. It seemed as if he was talking to someone of his own age.

“Your wife, God bless her soul,” said Nicolò, because he had heard people saying that she was always going to church and talked about the wonders of Heaven, “always said that when we die, we all go to a beautiful place and live happily ever after.”

“Don’t talk to me about such idiocies,” said the man.

At that moment, Nicollelo’s mother knocked at the door and he had to go, breaking off the conversation. Nevertheless, in spite of the brevity of the conversation with the strange, brooding man, and that he hadn’t really understood, he was moved, he felt questions had been raised, questions which he would never find the answers to.

Nicolò is still in bed. He stretches. Then he gets up. He’s thinking. He can’t believe it. How is it possible that his mind had buried all of these memories and he could now rediscover them, bring them back to life and relive them with such strength and clarity?

Next post, from chapter VII till chapter XI, the end of the first part

A Child from South Italy

thank you Miss Avery, your translations are quite welcome! Though Italian is my first language, it’s not my best, you have done myself and Francis’ readers a great service..i look forward to more of your translations.

thanks so very kindly once again..

franc

Dear Franc,

Thank you for your encouraging words. It was the first time I had ever translated anything that could be called literature, even though I had/have been translating for donkey years, so it was quite a challenge. For a long time now, I’ve also been working on another book of Francis’s “La particella seminale” which I hope to finish sometime. Unfortunately, it’s always a case of trying to fit it in between other commitments, of which I have not a few! So a few kind words are an extra stimulus to continue. Thank you once again,

Joy

Would you like to submit your ad on over 1000 ad sites every month? One tiny investment every month will get you virtually unlimited traffic to your site forever! Get more info by visiting: http://www.pushyouradonthousandsofsites.tech